Architects: Herbert Leeds, Alister MacKenzie

Walkable: The course is exceptionally routed for walking, though there are some decent elevation changes

Highlighted Holes: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17

Palmetto. Pahl-meh-toe. Simple word. Fun to say. State tree of South Carolina. It’s not the tallest palm in Arecales, but has costapalmate leaves that are some of the most intricate of its contemporary brethren. The palmetto thrives in the subtropics and, having evolved some 85 million years ago, is among the world’s oldest. It is complex, resilient, and adaptable: the perfect symbol for one of America’s oldest and most enduring clubs.

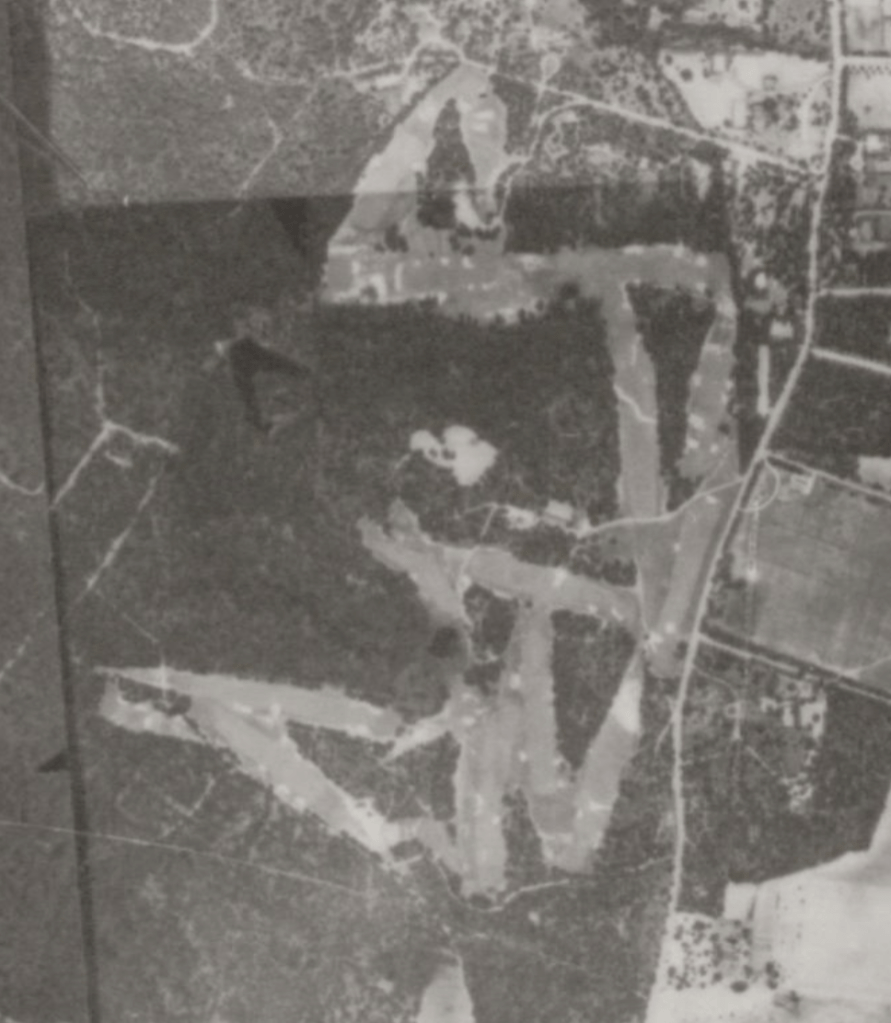

Founded in 1892, Aiken’s Palmetto Club has been touched by some of the most storied names in golf architecture. The original four holes near the clubhouse, now sixteen through eighteen, were built by founders William C. Whitney and Thomas Hitchcock. These soon turned into nine and then eighteen holes by 1895 when Herbert Leeds, the architect behind Massachusetts’ legendary Myopia Hunt Club, completed the routing with club pro James Mackerell. For almost forty years the course had sand greens; easy to maintain but out of date by the 1930s.

Following his work at Augusta National, golf’s great Alister MacKenzie designed new greensites and lengthened the course, but died before seeing the results. His work shines within the clever routing as the mounds and knobs that define his greens across the state line are ingeniously placed to allow for creative chips and approaches from the correct angles while deflecting halfhearted and lackluster attempts. Tom Doak’s description of MacKenzie’s work at Augusta is equally suited for Palmetto:

On nearly all of these holes, what makes the design so unusual is the concept of using tightly-mowed slopes as a sort of hazard, so that a borderline approach shot runs away from the cup or off the green and leaves a touchy pitch, chip, or putt, often up and over a ridge at the edge of the putting surface.

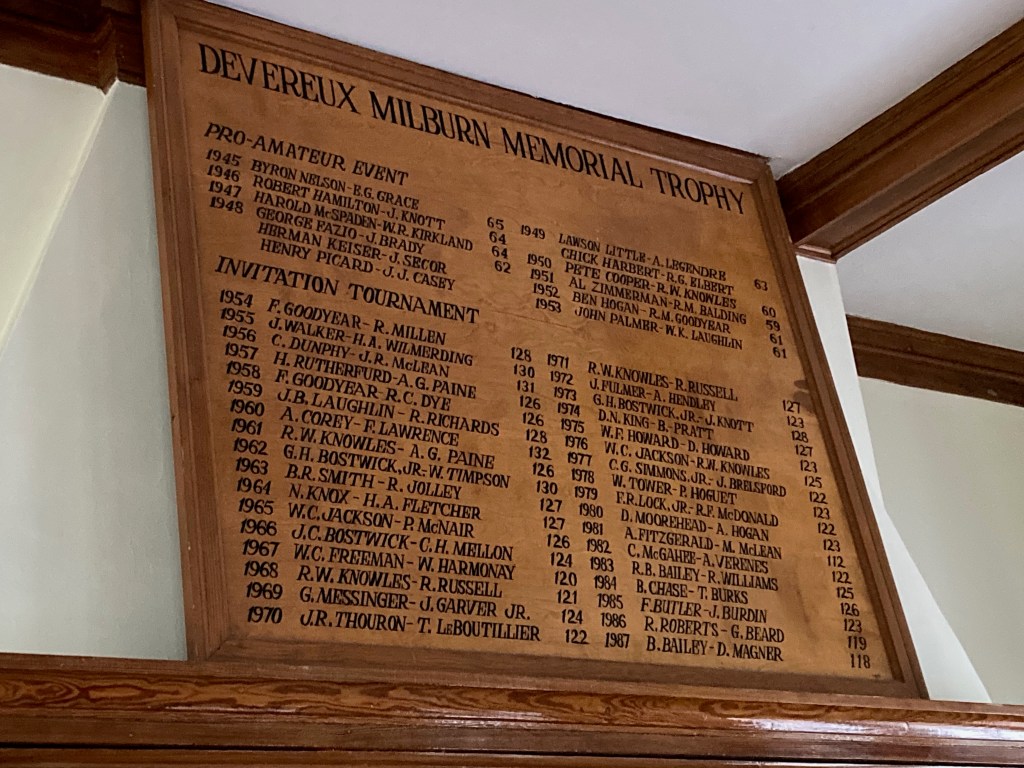

Built in the heart of Aiken and flanked by Hitchcock Woods, 2,100 acres of urban forest, the club is one of America’s oldest. Most impressively, it’s an incredibly friendly and unpretentious place that opens its doors to public play during Masters week for golfers to experience. In the early years of the Masters, competitors would come to Palmetto before Augusta for the annual Pro-Am, often winning more here than at the major itself itself. Past champions include the likes of Ben Hogan, Byron Nelson, and Lawson Little.

Palmetto is not overly long and doesn’t need to be, tipping out at almost 6700 yards. That it is home to multiple PGA Tour pros including Kevin Kisner, who grew up along the 17th fairway, is evidence of the challenge and variety of shots the course demands. The land is hilly, but not oppressively so, and the playing corridors are wide, but not overly permissive. Groves of trees divide many of the holes but never feel stifling or penal.

Its four par threes are diverse in length, verticality, and orientation. One is uphill, one is downhill, one is relatively level with no carry, and one is relatively level but all carry. The par fours are as strong and distinct as on any course I’ve seen. It’s no wonder that pros like it here as, excepting the tee shot on seventeen, ‘everything is right out in front of you.’ While that may be a subtle dig at other courses, at Palmetto it’s a compliment. What’s in front of you is question after question, decision after decision, and calculation after calculation. The fairway bunkers are well placed but not overdone and the quirk is there without feeling gimmicky. Its three par fives are also distinct from one another: long, short, uphill, downhill, straight ahead, and askew.

The highlight of an already exceptional list is the greens. There’s no question that MacKenzie knew what he was doing and architects who have worked on the course or provided input since (Rees Jones, Tom Doak, Gil Hanse) have respected the greens and left them largely untouched. Internal contours, mounds, knobs, and the importance of angles are all on display in these magnificent putting surfaces. The third at Minnesota’s Loop at Chaska takes inspiration from both the fourth and fifth holes in its contouring.

One (Lookout): From an elevated tee box near the practice green with the fourteenth green to the right and the Fermata Club in the distance, Palmetto starts you off in full view of the clubhouse. While they may not look it, the left and right fairway bunkers are in range. The crowned green is guarded at the front by two bunkers and is one of the few on the course where a miss long isn’t at least a half shot penalty.

Two (Whiskey): A large waste area short of the green provides some flavor but the four fairway bunkers are the major concern. Two right, one left, and a cross bunker that creeps into the middle all protect the elevated green that falls off all around. Its false front helps disguise the broad left to right sweep of the rest of the green.

Three (Southern Cross): Thus begins a stretch of holes that Ben Hogan called, “the best back-to-back par fours I ever played.” Trees protect cars on Whiskey Road and the golfer from finding themselves out of bounds or in an insurance squabble. The fairway bunker right makes for a difficult approach but the center of the fairway only slightly improves ones chances of finding the putting surface. A severe false front rides twelve feet (halfway!) into the green guaranteeing a back left or back right pin. The back right section is guarded by a bunker that one would be smart to avoid. A miss long leaves a delicate chip and the chance of missing the green altogether. Frankly, there’s no shame in laying up as an act of preservation.

Four (Red): A beautiful gnarl of native is all that stands between the golfer and the hole. The fairway kicks from left to right but a cross bunker lingers for anything hit too far. The greensite is stupendous. As is the case with nearly every green here, the surrounds are all cut to fairway height. A large swale on the right offers a myriad of options to try and get the ball on the green. A mound and valley left make things more interesting while the backstop can be used to great effect, assuming you don’t end up behind it.

Five (Palmetto): The fifth is deceptive. One fairway bunker guards the left side of the fairway while a grove of trees guards the right, but the green is bunkerless and the hole is straight away. The green is a masterpiece. I’m told that Gil Hanse softened the false front a little to add some more pin positions, but that doesn’t seem to have taken any of its character. Stay below the hole. Aim for the right side of the green. Hang on for dear life. And have fun. Thus ends a stretch of holes that Ben Hogan called, “the best back-to-back par fours I ever played.”

Six (Valley): From the tournament tees, the par five sixth is only six yards longer than the par four fifth. Well placed fairway bunkers keep you honest and three more guard the front right part of the green. The hole is direct but the green is tucked high and left like a castle keep. The hillock behind will corral shots in or frustrate anyone out of position.

Seven (Ridge): Delightfully devilish Herbert. This short par three benched into the hill falls off hard on the right and back with bunkers at the front left that hide most of the green from view. You must be confident in your yardage and trust your line to find the putting surface.

Across from the green is one of our favorite features here at Laymans: a pleasant walk between holes. Go up the hill along an old set of wooden stairs to the eighth tee.

Twelve (Pond): This tremendous par four snakes up the hill with three tall pines and a bunker that stifle any opportunity to cut the corner. The fairway slopes toward the only pond on the course, which Kevin Kisner keeps stocked to fish in. Palmetto is that kind of place. The green has subtle slopes and a series of crenelations at the rear that feign keeping your ball on the green. It’s like when someone drops something and you make a move as if you’re going to help them pick it up but know they’ll just get it themselves.

Fourteen (Crazy Creek): This long downhill par five with a dry wash that runs through and wouldn’t feel out of place at Huntercombe. The dry creek runs diagonally across the hole and will gobble up mishits or especially long drives. A tall pine grove lines the right side and a couple of solo trees patrol the left. The green is one of the more receptive on the course but slopes subtly from right to left until it falls off hard.

Fifteen (High): This 260 yard par four is perfect. No notes. It plays to the top of the hill on which the round begins before kicking toward a green that slopes hard from right to left. Big hitters may want to keep driver in the bag as any shot hit over the back is in serious trouble. The bunkers 60 yards out on either side of the fairway are also worth noting as that approach shot isn’t everyone’s cup of tea.

Sixteen (Berrie): To go from fifteen to sixteen you walk through the patio between the pro shop and clubhouse and across the front drive. At first glance it looks to be a flat par three with little interest, but that couldn’t be farther from the truth. The bunker left looks closer to the green than it is while the right bunker is up against it. The green is pushed up and falls off at the back into a trough that’s bisected by a pair of humps, one in front of the other.

Seventeen (Brae): The hole is entirely blind from the tee so the first shot is a leap of faith. The fairway runs out at 250 to 280 yards ahead of a swale that emerges from the left deepening and blocking the view the farther right you go. The green falls away on the left but has a raised back edge that can help keep balls in play.

Final Thoughts:

Palmetto starts with five consecutive par fours that are so good and so varied that you probably wouldn’t notice. They vary in length, starting short (389, 368), ramping up dramatically to 455, easing off into 388, before culminating in the 458 yard fifth. This stretch of holes alone would make a course notable, but sets the tone at Palmetto. They introduce the course’s complex greens, closely mowed surrounds, and importance of thoughtful tee shots. Courses around the country should look to Palmetto for ideas on creating sustainable interest around their greens without excessive bunkering to provide a wider variety of shots on a smaller budget.

Out here, no two holes are alike. No hole is indifferent. It’s nothing but fun from start to finish with a clever routing over bold property with greens that anyone would be lucky to play everyday. Palmetto is a special place and quickly became one of my favorite golf courses. Anyone know a member who’d like to host me at Myopia? I’d like to start the Herbert Leeds Society.

Further Reading:

Palmetto Golf Club: A true treasure steeped in golf history – Reid Spencer

Palmetto Golf Club: The First 100 Years published by the club

The Life and Work of Dr. Alister MacKenzie by Tom Doak

*Special thanks to PalmTalk.org, the University of Texas, and what’s left of the the National Parks Service for the cram session on the biology of palm trees.

Leave a comment